Odd and hilarious place names in Britain

Yes! These unusal British place names intrigue or give a giggle to many passers-by, like this lovely name Little Snoring, given centuries ago to a Norfolk village.

The origins of those names are deeply rooted in the fascinating history of Britain.

A great amount of British history: from the Celts through the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Scandinavians, and Normans to modern times – is displayed in Britain’s place names.

Some towns have received such bizarre names that no one can be sure what their origins are, for example the village of Pity Me outside Durham.

Water names – the Celtic influences

Two-thirds of England’s rivers take their names from Celtic

Even today, many hills and rivers have kept their Celtic names – particularly in the north and west, like : Avon, Derwent, Severn, Tees, Trent, Tyne – and Itchen, which later lent its name to the town Bishop’s Itchington. (Some of these names may even have come from the people who were here before the Celts). Often the names just meant ‘river’ or ‘water’, and sometimes no one knows what they originally meant; in the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, AD Mills calls Severn “an ancient pre-English river name of doubtful etymology”. The River Thames, comes from the Celtic word for ‘dark one’ or ‘river’.

There is less Celtic influence in the south and east largely thanks to the Anglo-Saxons. When they invaded in the 6th Century AD, they pushed the Britons to the edges and into the hills.

Fighting words – the Roman and Anglo-Saxon influences

The Romans invaded Britain as well, in AD 43. But their linguistic influence, like their culture, left less of a mark: they built towns and garrison outposts, but they never truly made Britain their home. Roman contributions to British place names come mainly through their Latinisation of pre-Roman names. The Romans called Britannia what we now know as Britain, Londinium was their name for today’s British capital city- London. The other major Roman contribution comes from the Latin castra (‘fort’). Taken into Anglo-Saxon, it became ceaster (‘town, city’, pronounced rather like ‘che-aster’) – which has mutated to chester (Chester, Manchester), caster (Lancaster, Doncaster) and cester (Leicester, Cirencester).

The Anglo-Saxons built a great number of forts – the word burh (‘fortified place’) gives Britain all of its –burghs and –burys – but what they really wanted to do was farm, build towns and conduct trade. If they encountered a forest (called a wald, wold, weald, holt or shaw) or a grove (graf, now –grove and –grave), they might clear it to make a leah (now –ly, –lay, –ley and –leigh). They would enclose land to make a worthig (–worth), ham (the source of ‘home‘), or tun (now –ton and the source of ‘town‘). As ham was more popular in the earlier years and tun later on, there are more –hams in the south, where the Anglo-Saxons first came, and more –tons in the north and west.

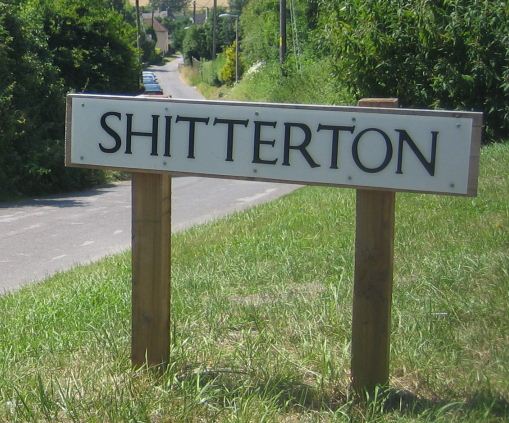

Shitterton – the name of this Dorset hamlet has Anglo-Saxon (and unfortunate) roots: it stems from the town’s stream, which once was used as an open sewer.

The Anglo-Saxons also liked to name things after themselves. The suffix –ingas (now shortened to –ing(s)) referred to the family, for instance, Hæsta’s folk settled at Hastings. Many a ham and tun were also named after a family, such as Birmingham, the ham of Beorma’s people (Beormingas). They also named geographical features for themselves, like valleys (denu) such as Rottingdean (the valley of Rota’s clan). In addition, before converting to Christianity, they named some places after their gods – Wednesbury is named after Woden.

Scandinavian language influences

Then the Scandinavians arrived. They started in the 8th Century with raids: Danes from the east and Norsemen, coming around Scotland by sea, from the northwest. They staged a full-scale invasion in the mid-9th century and began to settle in the areas they controlled. At the height of Scandinavian power in Britain, they controlled an area known as the Danelaw that covered most of England north and east of a line from Liverpool to the Thames – a line you cross at Watling Street (an ancient road) as you drive northeast toward Ashby-de-la-Zouch.

As well as oddly-named towns, Britain has streets like York’s Whip-Ma-Whop-Ma-Gate, which may come from Scandinavian for ‘Neither one thing nor the other’.

Ashby, like Appleby, has kept the quintessential mark of a Danish place name: –by, meaning ‘farmhouse’ or ‘village’. Both, however, also bear the marks of the Anglo-Saxons who where there first: the apple and ash trees. Also from the Danes came both (now booth), meaning ‘cattle shelter’; thorp, meaning ‘satellite farm’, now mostly with an excrescente as in Donisthorpe.

French influences

1066 saw the Norman invasion from France.

Yet, the Norman French did not settle in with the same comfort as the Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians, and not in the same numbers. The common people– made up of Anglo-Saxons, Scandinavians and remaining Celts – kept speaking English, which was still evolving and resulted in many French words, like Ashby-de-la-Zouch, the ‘ash tree farmhouse belonging to the Norman de la Zuche family‘ .

At that time, English again became the language of rule. The court resumed speaking English in the 14th Century; parliament returned to it in the 15th century. Finally, the stubborness of the Anglo-Saxon language won in the end.

All of those amazing changes can be observed in 60 miles, going from the Celtic hills, across the Anglo-Saxon and ancient Celtic towns, through the pre-Celtic, Celtic, and Anglo-Saxon rivers, passing the faint traces of the Romans, then into Danish territory, and finally finding the French nobility.

No Comments